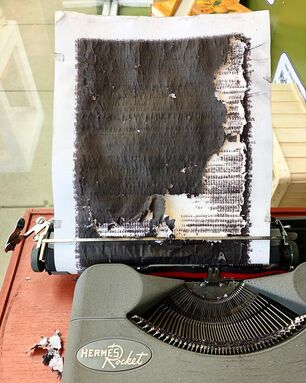

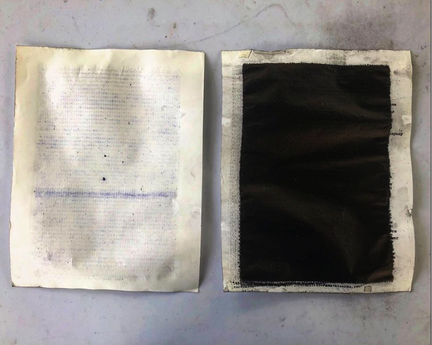

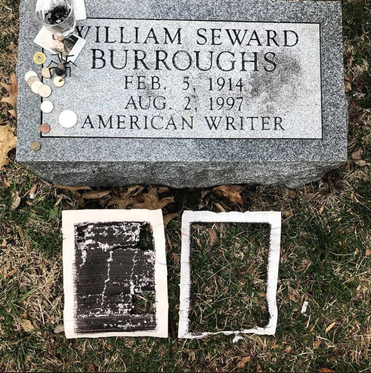

Youd began his project five years ago with Hunter S. Thompson's Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Since then, he has retyped more than 50 novels and works of poetry always following the same ritual. First, he finds a location (or locations) with a special connection to the author. Then, he proceeds to retype the work on the same make and model of typewriter used for its composition. Each performance is open to the public, which adds a voyeuristic and communal element to a normally private activity. And the final product? Youd is not trying to reproduce the work verbatim —that would mean simply copying and that is not what Youd is after. Retyping is not the end but a gateway into the personal and abstract process of reading, as well as a means to explore the relationship between writing and visual art. This is why he retypes the whole text onto two sheets of paper taped together and run repeatedly through the machine. When the work is finished, the two sheets, or what is left of them, are separated and placed side by side to create a diptych that is both the material remnant of the physical process of typing and a two-dimensional visual analogue of the abstract experience of reading, one that bears an uncanny resemblance to the two pages of an open book.

In a literal sense, however, the diptych is the "relic," the reliquiae or remains of the physical act of typing, what is left over after the meaning has been absorbed by the reader. The very existence of a material residue suggests that Youd makes a distinction between the literary "work" and the "text". The work is the product of a particular authorial experience and intention, and cannot be repeated, whereas the text can be copied, manipulated and recreated. In other words, the work is the content, while the text is its external machinery: the paper, the ink, the signs on the page. Youd's idea of a "devoted" reader is someone who "stays with the words"(2), someone who focuses on the meaning. But "staying with the words" also implies a certain concern with the physical, material aspects of the text. It is this concern with the physical text that makes Youd's performance diptychs more than just debris, the unwanted residue of his performance. They are also evidence of a time before the digitalization of writing, when we felt that (perhaps wrongly) the meeting of ink and paper signified a kind of sacred contract between the writer and his or her text. Now we fear that our words will be forever lost in the digital void (probably another misconception). Perhaps inadvertently, Youd's diptychs evoke both the permanence and ephemerality of the written word.

Cheever's diptych above, for example, with its solid square of ink and faint, illegible markings, suggests both the density of the text and its impermanence, while Burroughs' (image below) calls attention to the violence implicit in the act of typing itself: the top layer has almost been obliterated so the whole novel is now compressed onto a rectangular ink stain

with the texture of burnt bark — darkness visible.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed