What I want in poetry is a kind of abstract photography of the nerves, but what I like in photography is the poetry of literal pictures of the neighbourhood. (John Koethe)

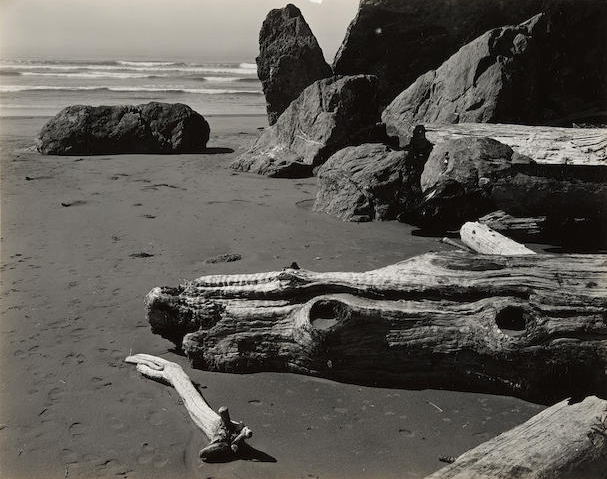

Is there such a thing as a “literal picture”? It seems to me that any picture, no matter how matter-of-fact or close to the real thing, has the potential and the power to take us beyond our immediate reality. Like poetry. Implicit in Koethe’s call for poetry to be more like photography and for photography to be more like poetry is an awareness of the close kinship between the two arts. There is poetry in the literal. In the same way, the literal haunts the poetic. A photograph’s impact comes from its ability to take a slice of reality and present it to the viewer in all its concreteness, its literalness. A moment snatched out of the flow of life and frozen in time. Wim Wenders notes how photographs “invite us” to see things in detail. Even a blurred image is an invitation to explore, and more importantly, experience the quality and texture of an object that is out of focus — to sense the quality of blurriness. Sometimes what we experience in a photo is the complexity of the object captured by the photographer; sometimes it is its simplicity that captivates us. In both instances, we are moving from the known to the unknown, which is also something metaphoric language does, and poetry in general — or the “unthought known,” Christopher Bollas’s beautiful formulation for what has been experienced but not assimilated by the conscious mind. Much of what we see in a photograph (or what we sense in poetry) is a re-discovery, a bringing back to awareness of something that we didn’t know we knew, or just didn’t remember, and yet we felt was there all along. Something that is yet to be known.

So when we talk about the poetry in a photograph, we are talking about the way a “literal picture of the neighbourhood” can evoke the known and at the same time reveal the unknown. Or perhaps, its real power stems from its ability to present us with the known while evoking the yet-to-be-known. I think this power to excite our imagination stems from the photograph’s special relation to time. Wim Wenders calls photography a “time capsule,” while Geoff Dyer refers to a picture’s ability to hold the “ongoing moment” within its frame. It’s not so much that the camera arrests the moment, which it does. Time contained within in a photograph is not static but continues to “generate energy,” as the poet Penelope Pelizzon suggestively puts it, that “may intensify as more layers of time accrue around it.” Koethe’s “abstract photography of the nerves” vividly conveys this “ongoingness,” this pulsating energy. It is as if time thickened before our eyes. It is a strange feeling, because, unlike painting, which still retains a certain three-dimensional quality, photography is unabashedly two dimensional. Granted, not all photography is concerned with time or with transcending two-dimensionality; some photographers revel in the very flatness of the medium. But for most viewers (for every viewer, really), photography is inescapably bound up with time and our desperate need to hold on to it, to preserve it.

For me, a photograph is an invitation to focus my attention on these elements that always appear to be in tension or opposition — the literal and the figurative (or poetic); the known and the unknown; time arrested and time expanded; stasis and continuity — not as opposites but as separate moments in a continuum of experience My academic training taught me to see the world according to these binaries, or at least to recognize that these are the categories through which most of us look at the world. But now I want to think less and experience more, or to think in a different way. To immerse myself in the texture of experience. Perhaps it's no coincidence that my interest in photography has grown as my yoga practice has evolved. It is in stillness that we can begin to experience the “ongoingness” of the present moment, its connection to the past and the future, to feel the arc of our whole life as it presents itself in that instant, when we are just the interval between heart beats, the space between inhalation and exhalation. This rhythm is the rhythm of nature, of organic matter, of growth and decay. But a similar pulsation, a similar layering of time can be sensed in the inorganic. A photograph does not distinguish between what is alive and what is dead, between organic and inorganic matter. In the “thickened” space of the frame, everything is still and everything pulsates with energy. The literal is infused with poetry and the poetic illuminates the literal.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed