I've put together some art works by Salt Spring artists. These are works that evoke a particular feeling or thought, or pose a question. My aim is to get closer to an understanding of art as an expression of the artist's imagination -- of his or her imaginative engagement with the world. Is my own engagement with the works an imaginative act?

What does it say to me? : "I want to create a shape that evokes and at the same time obscures its referent in the real world."

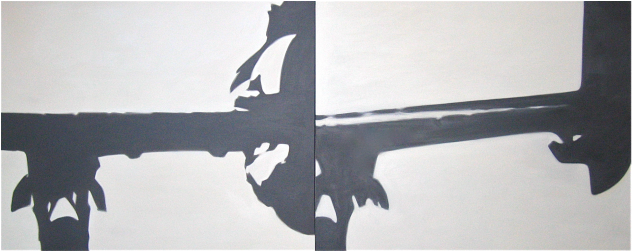

The first time I saw this piece, several images began to form in my mind: first a bridge, then a gun (did I see a trigger on the right-hand side?). A closer look revealed a mask, some facial features, a cartoonish drawing of a face. I was quite disappointed with my inability to see more complex and interesting figures in this mesmerizing work. Why do I find it mesmerizing, I wondered? Even slightly disturbing in its refusal to be explained easily. Is it because I can't really see anything that points to an object in the real world? As it happens, there is a referential point, but the artist has manipulated perspective and composition in such a way that, when we find out what this object is, we only catch a brief glimpse of it before it disappears once again. The question that emerges then is not "what am I looking at and not seeing?" but "What am I not looking at and seeing after all?" And there is no answer to this question, or no single answer, just the question of perception and how our intellect wants to find a point of reference while our imagination seeks finer textures and concatenations.

Representation or imagination? A dialogue, an oscillation between the two.

What about the title? How does the title, "Lancaster (Falling out with Love Again)" bear any relation to the painting? Is this a work about "love" or about what it feels like to "fall out" with the idea of love? Maybe, like the object that inspired the image (an object that shall remain hidden…), the title was inspired by a specific event in the artist's life, a break-up perhaps. If this is the case, we can think of this break-up as the reference point around which to construct an interpretation of the work. After all, nothing in the piece itself says that it isn't "about" love; nothing in it says that it is, either. The title is a playful reminder that art, as Susan Sontag tells us, cannot be easily explained or paraphrased. To interpret a painting or a poem we need to cut out content— life details, historical context, technical explanations or artists' statements— "so that we can see the thing at all." My background is in literature and textual analysis. I could, if I put my mind to it, offer a more or less convincing interpretation of the relationship between the title and the painting that would demonstrate that love is its central theme. But, would that illuminate the painting any more? Would it make its meaning intelligible for the viewer? J. Robert Moss's painting raises interesting and relevant questions about the importance of meaning, reference and the value of interpretation in art. And it does it quietly, by being nothing more and nothing less than what appears to us when we finally realize that what we see is not necessarily what we are looking at.

Now, what do you see?

Acrylic on panel.

After the curfew comes freedom, a release. Emergent shapes and shades of colour. If I read the canvas from left to right, like a piece of writing, I see lines forming, then a splotch of ink -- more like a glob or a pool of ink. I like the onomatopoeic words that the painting is suggesting to me: splotch, glob, drip, swish. I feel the movement of the brush on the surface and I follow the contours. Not so different from writing. Underneath an eye forms. Something that resists the pull of geometry, that tries to resist. What do we see when we look at an abstract painting? Shapes. What do we hear? The movement of the brush. I keep reading. Cubes and rectangles begin to appear. Now we have some shape, some order, but is there any sense? After the curfew ends, we prepare for its return. It's a human compulsion, to be contained, to contain.

I am looking at a shiny photograph of a very tactile painting, actually. Tactile in the sense that it asks to be touched: its textured surface calls me to feel it with my hands, not only with my imagination. The brush work is rough. Irregular strokes. After the curfew I don't care about what this is going to look like; I am only glad I can step outside again. Planks of wood of the kind you find in a construction site. Rock surface. Does it want to be absorbed through my senses, instead of my imagination? Is my attempt to read the painting an attempt to tame its energy, to control it by giving it some meaning?

Abstract painting can sometimes maintain a very tenuous relation to the real world. As my eyes move around the surfaces that keep emerging, I want this painting to have some relation to the real world. I want to see an industrial landscape, but I only see a disintegrating landscape. A disintegrating landscape of the imagination.

What does it say to me? "I'm trying to dissolve shape into colour and texture. Against the compulsion of form."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed