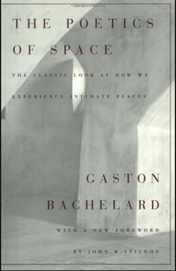

It was a powerful experience. The brightly-coloured life-sized canvases were curiously seductive and overwhelming in equal measures. Their seductiveness for me lay in the Pop-Art -inspired bold colour scheme and use of everyday objects, but, mostly, in the illusion of depth induced by Wheston's skilful use of perspective. At times, it felt as if the paintings were beckoning me to step into their spaces. But, as I got closer, I had an eerie sense that the objects were suspended on a flat plane, ready to spill out and fall on top of me. This curious visual effect shifted my attention away from the overt theme of the exhibition and made me focus instead on the role of space in the paintings. Yes, I was looking at a series of carefully-organized and crafted tableaux in the style of old historical paintings and portraits. In these traditional works, the aim is to represent reality while at the same time shaping it and containing it within the boundaries of a frame. I realized that Wheston's paintings also articulated this theme of containment: how our living spaces, like the space of the canvas, act as containers, vessels or repositories for our lives ; how our rooms -- the real ones and the ones we imagine in art -- can harbour and at the same time give expression to our deepest thoughts and desires, projected onto walls and surfaces, hidden in corners or contained in the objects that we choose to fill their spaces with. As Gaston Bachelard reminds us in The Poetics of Space, our living spaces, and those represented in art and literature, have their own "poetics," their own "imaginative way of being." They are more than representations of our internal worlds. They constitute a topography, a map of "our intimate being," where complex and contradictory desires co-exist, like the desire to accumulate to excess, and the need to contain and control. Our living spaces are always sites of tension and ambivalence, of the ebb and flow of desire.

So, how has Wheston imagined this map of desire in her paintings? What kind of space has she created to articulate its complexities? A contained and organized space that, on closer inspection, yields something more. The painting at the top of this page, "Roast Beef," is the one that best expresses this dynamic, for me. It presents a kitchen where objects abound but don't crowd each other, where everything has a place and nothing overflows. Even the garbage has its proper place: in the can, on the floor. The woman standing at the front, holding a plate of roast dinner, is strangely immobile, lifeless, yet has a commanding presence. She is the point around which all the other objects accumulate. Hoarding is the external and exaggerated expression of human desire, which, psychoanalysis tells us, is fundamentally impossible to satisfy. Wheston imagines a space where the desire to accumulate objects can somewhat be tamed within the space of the canvas and the boundaries created by the frame, captured in one single static shot. Only that there is something compelling and strangely alluring about the objects displayed, their colours, the soft yet firm brush-work that creates the feeling of volume and space that calls the viewer to look closer, to reach inside and touch. Suddenly, the woman was no longer flat and lifeless but full and rounded, exuding eroticism in her skimpy nightdress. The more I looked at her, the more I realized that her body was uncomfortably contained by the lines that form her shape on the canvas. Shadows began to emerge, colours appeared to dissolve a little ; the water bottle began to look strangely misshapen. The illusion of containment and organization was beginning to soften, allowing the exuberance of the painting to shine through : the textures and colours, the softness of touch, the loving care employed to paint each and every object -- the artistry at work. That's when I felt the compulsion to walk "through the looking glass," only to be confronted by the reality of a flat surface. I was back in the realm of structure and form, of straight lines and composition. But now the woman was looking straight at me with a soft yet slightly ironic expression, as if saying, "See? You also live in a place like this, full of stuff. You also feel the pull to let go, and the pull to keep everything in place. And you can't let go. Or you won't let go. But sometimes you just have to. See? This is your imaginative space, too."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed