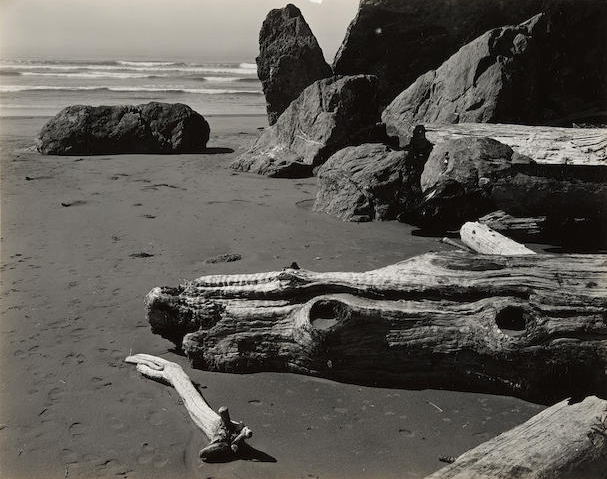

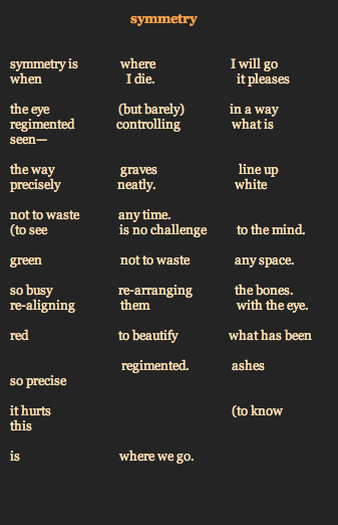

when the water is calm enough to capture the shadow of some tree branches dangling above.

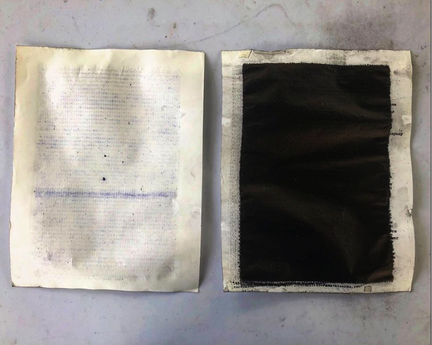

You see their contours dissolve, like ink poured on water

and, for a second, you think you can see the shape of a heart emerging,

its surface veins exposed, each beat pushing the waves back, out into the ocean ...

You wouldn't know it's there, hidden under the current.

Then you think that this sudden apparition only makes the waves more determined to return to the shore

The ocean knows its own power

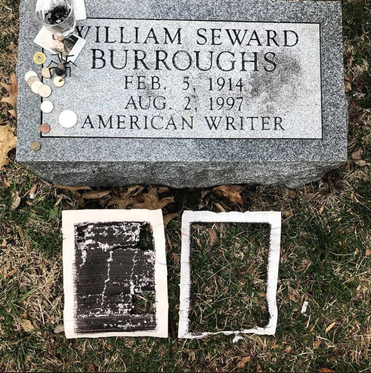

But does it know the power of a beating heart? I wonder

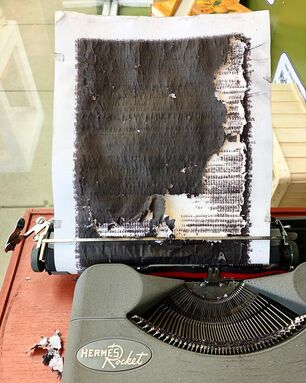

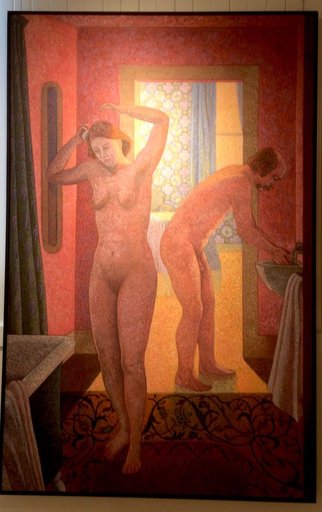

The camera is poised just at the right angle, waiting for the right moment to expose

to reveal

The heart at the centre of things.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed