Daniella Elza lives in Vancouver. This is her website: http://strangeplaces.livingcode.org

Fugitive: given to or in the act of running away; moving from place to place; fleeting (OED).

Symmetry: agreement in dimensions, due proportion.

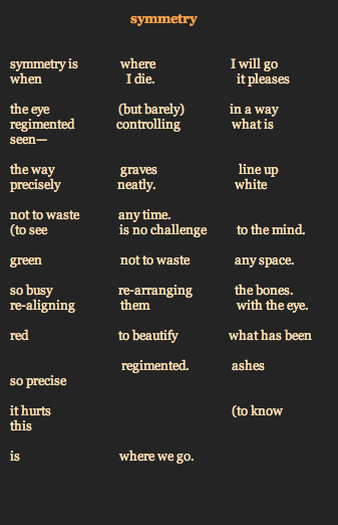

Symmetry "pleases/ the eye," but "barely." The certainty that symmetry provides -- everything has its due proportion, there is order in the universe—is soon, almost necessarily, followed by a bigger, more inescapable certainty: we die. Our graves trace the same motif, they "line up/precisely neatly" (lines 6-7) Our "bones," our "ashes/so precise." It "hurts (to know." And, yet, we find some comfort in symmetry. It exists beyond us: "symmetry is where I will go/when I die" (1-2). A statement of fact. Facts are comforting. They have their due proportion, "the way/precisely," "so precise/it hurts"(16), because symmetry is also death. We can arrange graves and bones, but they remain dead, even if the arrangement is beautiful to the eye. But the eye can also be alive. Our inner vision—our imagination—has the power to transcend our finite physical existence. In Elza's poem, the vision is Platonic. The world that appears to our senses is only a copy of a more "real" and perfect realm of forms or ideas that are eternal and changeless— not unlike symmetry.

Elza's vision in this poem, however, is far from changeless: it is dynamic, unpredictable. Elza conveys this dynamism by breaking up the lines and creating three not-quite-symmetrical word columns, a pattern that frees our eyes— "the eye/regimented"— to roam freely across the page, tracing new arrangements from left to right, from top to bottom, across the page, moving up and down, from word to word, fragment to fragment, sentence to sentence. Read in this way, the poem becomes a chessboard, our eyes moving the pieces to create surprising combinations. Line 8 reveals aphorism: "not to waste any time is no challenge to the mind." There are also some Beckettian moments (I see Beckett everywhere): in the third column: “I will go/it pleases/in a way/what is" reminds me of Beckett's characters, so stoic in the face of death, yet so chatty, everything has to be processed through language, in the mind, "to the mind. /any space. the bones. with the eye."

I realize I am playing with the language of the poem, "busy re-arranging the bones" (line 11), these "bones" that have escaped their symmetrical "graves," the container of traditional poetic form, to roam free for a little longer, meandering, divagating, taking unexpected turns, having some fun, I hope. It must get boring, "the way graves line up" (line 6).

And I think about the reviewer's words again, "Daniela Elza shapes an unusual format to convey the fugitive nature of words"—not to contain but to convey, to give expression to the impermanent and changeable nature of language. Poetic form, by definition, seeks to give shape to the flow of language. Elza's poetic shapes, with their gaps and discontinuities, their unusual line breaks, their idiosyncratic use of typographic marks and their tendency to group words in new and strange combinations, are designed not only to convey the "fugitive nature" of language but also to "re-align" the way we see. After all, there is no escape from "symmetry," that much we know. But we can choose to look at it in a new and surprising way. That much she knows.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed